Q&A with TOMODACHI Program Participants and TOMODACHI Alumni: ʻĀlika Guerrero

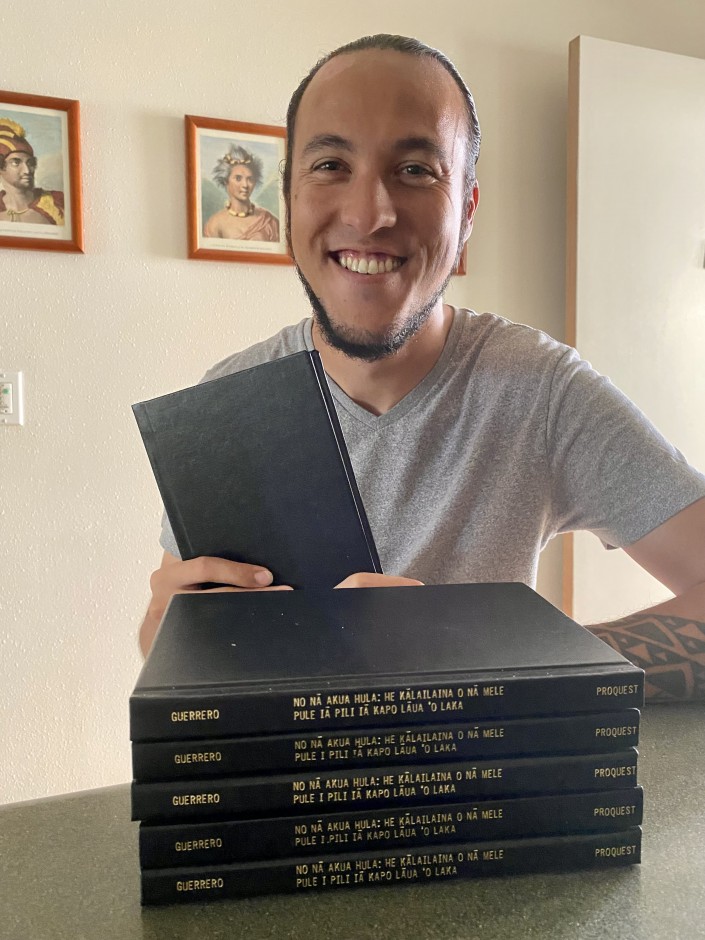

For this interview, we talked with ʻĀlika Guerrero, an alumnus of the TOMODACHI Inouye Scholars Program 2016 Program. ʻĀlika is a teacher of Hawaiian language, culture, and history at Kamehameha Schools Maui, a school for native Hawaiian students. He recently published his first book “No nā Akua Hula: He Kālailaina o nā Mele Pule i Pili iā Kapo lāua ʻo Laka”, and his goal is to contribute to the efforts of keeping the Hawaiian native language alive and active.

Q1: Can you tell us a little bit about your recently published book?

The name of the work that I just published is No nā Akua Hula: He Kālailaina o nā Mele Pule i Pili iā Kapo lāua ʻo Laka, which means The Gods of Hula: An Analysis of the Prayers Associated with Kapo and Laka. This work was the culmination of my master’s thesis that I’ve been working on for quite some time and finally, it’s been published and available. But it took quite a few years to put together. The work is built on the gathering of 107 different prayers for our traditional gods associated with the hula, and many people know about the hula, but not too much is known about the religious aspects of Hula. I wanted to take the time to look deep into the archives at the Bishop Museum, at the Hawaii State Archives, at our Hawaiian language Newspaper Repository, and to bring these prayers back into our consciousness. So the work provides all of these prayers that I gathered. But I also offer an analysis of their meanings and the information that they have about our culture, about our language, and where we are right now. In Hawaiian culture, there’s a very great desire to learn things about Hawaiian spirituality and traditional religion. So I hope that this work is interesting to people, and it contributes to our efforts here to revitalize Hawaiian language and Hawaiian culture.

Q2: Is your book written entirely in the native Hawaiian language?

Yes, it is, and that was one of the aspects I am most proud of. When researching something like this, it’s very important that I do so in our own language. I also want to promote the idea of normalizing the printing of books within our own language and making these resources available to our community.

Q3: What made you decide to participate in the TOMODACHI Inouye Scholars program?

I was a student at Ka Haka ʻUla O Keʻelikōlani which is the Hawaiian Language College at the University of Hawai’i Hilo, and the opportunity for this program was presented to our college, and any of the undergraduate students at the time were eligible to apply. When I heard about the program, I thought it was a very fun and unique opportunity to be able to travel to Japan. But I also thought that it was extremely valuable to go with my classmates, who were also passionate about language and culture revitalization. I felt that it would be a very unique program for a group of students and faculty members who only spoke Hawaiian for the entirety of the trip. For those of us who are committing our lives to revitalizing our language and culture, I thought that it would be a unique opportunity to take the things we were learning and the skills that we had, and to now go, not just outside of our school, but abroad across the world. And I don’t know when the last time that a group of people who only spoke Hawaiian the entirety of the trip traveled to Japan was. But I thought that that was something that I wanted to be a part of and make those unique memories and connections with not just my classmates, but the people we met.

Q4: Do you have a favorite memory from your time in the program?

There’s a couple, but one that really sticks out to me was when we went to Hokkaido University, and, you know, we’re from Hawai’i, and it was snowing. And so for us, that was a big deal. It was the first time we went to Sapporo, and I know that was the first time that I had seen snow falling. We got off the bus, and immediately we all ran out into the huge open field of snow, and we had a huge snowball fight. We were in the snow, and I remember we were taking our jackets off, and because it was an experience that we had never had before, I just remember that moment of everybody, even our professors were involved. And it was such a fun time. That’s an experience that many of us wouldn’t have had without TOMODACHI. I’m really thankful for that time that we had.

Q5: What did you learn from the program?

This is about seven years ago now, but one of the most striking lessons I think that we, as a group took away, was that, we’re so immersed in learning our language and culture that sometimes you really only get true perspective of its value when you’re now trying to hold onto it while you’re in a new place. For example, we experienced some major cultural differences. One of the big ones in our culture is that many people have tattoos In Japan, they are accepted in some places and not in other places, and it taught us about ourselves. By that same token we learned about the native people from Japan, the Ainu, and they also have tattooing in their culture, so we were able to relate to them in that way, so it gave us a true perspective. It also allowed us to see certain mannerisms, behaviors, and certain cultural components of the Japanese people that were very similar to our own. And again it caused us to think, “Oh, we also do this. Why do we do this?”. Those kinds of connections, and observations really only happen when we’re somewhere new, and when we are challenged to be a part of this other culture. That was something very new that I don’t think I would have learned unless I traveled with my classmates on that trip.

Q6: What was it like being able to learn more about Hokkaido and the native Ainu language and culture as a native Hawaiian speaker?

One of the things that it reminds you is that as a native and indigenous person or people, you are not alone in the world and in your experience. Not just the trauma that’s associated with being an indigenous and native person, but also with resilience. When we met those professors who were dedicated to teaching and revitalizing the Ainu language, and when we met Ainu people who practice their culture daily, it’s a reminder that what we do is really a global movement for indigenous people, and the rights of native people. We live thousands of miles away, but when we find one another that we have something in common, and we have a common goal. It was very interesting to find like-minded people of an entirely different culture.

Q7: Can you tell us a bit about your goal of keeping the Hawaiian native language alive?

At this point I’ve been studying Hawaiian language and Hawaiian culture for my entire life, and so I’ve really dedicated my whole life in terms of my educational and career goals to being part of this revitalization effort. My family has also made those same commitments, including my wife. It’s a lifestyle for us, even in the work we do outside of our professional career. For example, my wife and I teach Hula. We only teach Hula at our school through the medium of Hawaiian language. It’s something that we and I are very passionate about, and it has been such a meaningful thing in my life. I want to make sure that if I can help in any way to give that same experience, this same knowledge, and I can instill this same passion in other young Hawaiian students, then that’s something that I really want to be able to do.

Q8: What has your experience been like as a Hawaiian language culture and history teacher for native Hawaiian students?

I consider myself very privileged and very lucky to be in a position where not only am I teaching Hawaiian language, history, and culture, but I am able to teach them to native Hawaiian students, and only native Hawaiian students. I currently teach back at my Alma Mater, where I graduated from, a school that’s only for native Hawaiian students, and it’s like no other school in the world. It’s unique in that way, I’m able to speak to and to teach students who I can share this same experience with. I’ve sat in this exact classroom that they’re learning in, in this very same school. I can talk about my personal experience as a student, as an adult, as a teacher. This position comes with a certain responsibility, and I always try to keep that in mind, that I’m very privileged and lucky to have this responsibility of being one of their teachers at this unique one of a kind school, not just where I graduated, but where I grew up, where I live. I get to work in my community, with people and families that have been connected to mine that I’ve known forever. I’m just very lucky to be here.

Q9: What are some of the challenges within your community, and what opportunities do you think the TOMODACHI or the U.S.-Japan Council can do to help address that issue?

One of the issues in our Hawaiian communities is one of the ones that I and many other Hawaiians have really been working on, which is the revitalization of our language, history, and culture. There are other indigenous people out there, there are the Ainu we spoke about, there are the people of Okinawa, the indigenous people there, and we need advocacy, we need space, we need one another. For the situation in Hawaii as an occupied nation, we need the United States to take responsibility for the role that they’ve played. I would encourage the country of Japan, and anyone listening to also take responsibility, so we can move forward towards reconciliation. I would rather get into a discussion about how we move forward? What does reconciliation look like? How do we rectify this situation? And ultimately, what does the future look like for the indigenous people, first nations people living in the United States, and what can be done to help? I think if the U.S.-Japan Council and TOMODACHI found a way to bring us together and support our efforts to be connected to other indigenous and native people around the world, that would be great, because that’s really the help that we need. We need to be empowered. We need an accelerant. We have passion. We have the people out there. We need that support in a variety of different resources or ways. That’s what we need to make it happen.

Q10: What does TOMODACHI mean to you?

When I was a young person I had a mentor who told me at a very young age that you can never have too many friends, and their reason for saying that is, you never know. You never know when later in life, a year from now, ten years from now, 50 years from now, when you’ll need that friend and the unique skills and experiences they have. And with TOMODACHI, we live in this global world where now we’re able to connect with people thousands of miles away. We’re able to share experiences, insight and knowledge. What friendship can really mean now, and how much we can do when we activate friendships across the world. Just in Hawai’i, we’ve seen the power of those relationships when we have, for example, different cultural and political movements in Hawai’i, we’ve seen movements of support across the world. That’s to me what TOMODACHI means. It means a commitment to one another when someone is in need of support. We can be halfway across the world, but we’re not that far away. We can find something we have in common, and something that bonds us together. That was the message that I got when I was on that trip. That was the experience that caused it. I was invited back in 2017 to speak at the reception in Tokyo, and after I was done speaking, I was able to connect with Japanese Americans living across the United States, and we spoke about common experiences. Those kinds of things, I think, are really what our world needs. We need those kinds of experiences, with one another. We find out, we’re all just so similar, we’re more similar than we are different. We have much more in common than we realize.

This interview was conducted by Hannah Fulton on October 5th, 2023. Hannah is currently a TOMODACHI Alumni Program Intern and is an Alumni of the Toshizo Watanabe Study Abroad Scholarship Program 2022-2023.

This interview was transcribed by Aya Kaneko, TOMODACHI Alumni Program Intern since September 2023.